Why Artists are Needed at Research Institutions

By Reinhart Meyer-Kalkus

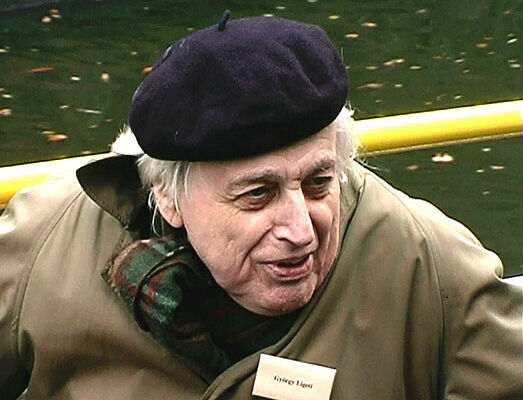

Since its founding, the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin has invited artists, including writers, filmmakers, dance and theater people, and composers, to be Fellows. The composers are perhaps the most conspicuous group; a whole Parnassus of contemporary music has been here. The group has included: Josef Tal, Alfred Schnittke, Hans Werner Henze, Wolfgang Rihm, Luigi Nono, Luca Lombardi, György Kurtág, György Ligeti, Helmut Lachenmann, Isabel Mundry, Jörg Widmann, Thomas Larcher, Hans Zender, Toshio Hosokawa, Jonathan Harvey, Mauricio Sotelo, Mark Andre, and Klaus Ospald.

Like other Fellows, composers at the Kolleg have the opportunity to concentrate on their work for 10 months while profiting from the stimulation of other Fellows. The hope of Peter Wapnewski, the first Rector, and his successors, who believed in the mutual inspiration between research and the arts, was that they would be the leavening agent in the Fellow group.

To take stock of these interactions, however, one must look and listen very closely. A superficial impression might be that artists and researchers each pursue their own projects and that when they come together at common colloquia, at daily meals, or in other undertakings they communicate in small talk and, at most, about contentious political topics, especially when current events lead to the latter. Strictly speaking, artists almost never influence what researchers calculate, conceive, or look for in historical sources while researchers only infrequently influence what artists create; the two realms differ too much in their goals and methods. Nor can it be affirmed that artists possess a uniquely refined social, political, ecological, and moral conscience. Such critical sensitivity can also develop in researchers. On the other hand, there is no question but that artists are valued as provocateurs, entertainers at summer and farewell parties, and providers of chamber music but all that is rather a different matter.

A potential problem is that many composers have difficulties producing in their accustomed rhythm in a novel environment. The distractions, especially in restless “transshipment points” of ideas like the Wissenschaftskolleg, are so great that the artists often neglect their own work on their current commissioned composition. “Not-Composing at the Wissenschaftskolleg” is how the refreshingly provocative Helmut Lachenmann titled his own yearbook report for the Fellow year 2001/2. And the year before, György Ligeti had to return to his Hamburg residence for 6 weeks in order to complete a commissioned piece, the 18th Etude for Piano (“Canon”). Only there did he find the necessary seclusion from external stimuli. As he once said himself about trying to work at the Wissenschaftskolleg, in the morning he had to remain undisturbed by gracious personnel bringing him coffee. Instead, he had to be able to alternate between his bed and his piano, if possible still in his pajamas and unwashed; only then could he fully concentrate on composing. Apparently, asociality and “a bit of dirt under his fingernails” were simply a necessary part of his creative routine.

Among the traces Ligeti left at the Kolleg are his co-Fellows’ reports in the institute’s yearbook. In more than a few of these reports, he is described as the real attraction and human center of his Fellow class. One of his apartment neighbors, the English-Australian economist Robert Wade, even published a report on his conversations with Ligeti in the “Economist” in 2001: “At lunches in the Wissenschaftskolleg, Mr. Ligeti has been a star, engaging voraciously in conversation with all comers on almost any subject in one of six and a half languages (Romanian, Hungarian, German, French, English, Swedish, with a musician’s Italian counting as half). Mostly, he prefers to talk about science. He is a friend of Benoît Mandelbrot, a founder of fractal geometry – the study of figures generated by successive simple operations such as division – whom M. Ligeti sought out after concluding that he had been using fractal patterns in his music for years. A mathematician manqué, Mr. Ligeti likes to say, ‘I am not a musician, I am a scientist.’ This is not simply a boutade, for he takes an unfashionably objective view of his work, one in which communication seems to play little part. At a lunchtime set-to recently about who it is that artists create for, one person mentioned that their poet-husband wrote for 30 people who could understand his work. Someone else cited an artist who worked strictly for herself. Mr. Ligeti cut in, ‘I create neither for an audience nor for myself. I create for solutions.’ Luckily more and more of us can hear how right his solutions sound.”

In such conversations, Ligeti avoided talking about the compositions he was working on. Whenever someone turned the discussion to them, he responded evasively with anecdotes and humorous quips. What especially interested him instead were the similarities and dissimilarities between scientific and artistic work, between problems and solutions in the one and the other, between proof and coherence. During his Fellowship year, he wrote the acceptance speech for the highly remunerative Kyoto Prize that he received the next year. It was titled “Between Science, Music, and Politics”. His used his stay at the Kolleg to come to terms with his ideas about those questions that had accompanied his life as an artist and to test them in discussions with scientists.

In his youth, the young Gyuri wanted to study chemistry and physics in Klausenburg. He dreamed of discovering the molecular structure of hemoglobin. A quota instituted against Jewish students in Siebenbürgen, which had been administered by Hungary since 1940, left him only the chance to study composition at the music academy – an absurd administrative chicanery but one to which we owe one of the most significant musical oeuvres of the 20th century. But alongside his compositional works, all his life Ligeti followed natural scientific and mathematical research with passionate interest. He knew no greater pleasure than to converse with quick-witted scientists. None of the 40 Fellows in his class at the Kolleg was as familiar with the others’ research plans as he was, and none could involve them in specialized discussions in their own fields as he could: “Oh, you are a specialist in Tibetan art? I love this art. But tell me, which part of this art are you working on, the North or the South? And which century?”

On the other hand, Ligeti tended to keep his distance from researchers in the humanities and social sciences. As the son of a positivistic-minded generation in the 1920s– his father was “an atheist and a true believer in science” – truth for him was synonymous with evidence tested by experiment and falsification, which was ultimately synonymous with natural sciences. He was unwilling to admit that philosophy could have its own valid procedures and conclusions; he regarded it as a kind of pseudo-religion. Dorothea Frede, a philosopher in his Fellow class, looked back and remembered his “always productive mistrust … of every philosophy. His pleas contra omnes philosophos, their jargon (or terminology), their dogmatics, their perversities – one wouldn’t wanted to have missed them.” As it was, with his co-Fellow Dieter Henrich, of course, philosophical themes like subjectivity and self-consciousness were on this class’s agenda of questions, to which Ligeti responded in part with defensive irony, in part with wrathful polemics

He saw researchers in the humanities as being under the spell of charlatans like the French post-structuralists, whose embarrassment through the so-called Sokal affair at the end of the 1990s gratified him immensely. In regard to social sciences like law, political science, economics, and sociology, he was curious, but likewise full of mistrust. As someone persecuted in various phases of his life for political and ethnic reasons, he was a sworn enemy of all ideologies and every totalitarianism. His idiosyncratic reaction to everything that had even a whiff of dogmatism about it was the other side of his quasi-scientific pleasure in discovery: “All my life I’ve found dogmas uninteresting,” he once wrote. “To push forward into undiscovered areas is what I regard as my primary task. How complex forms and structures develop out of extremely simple processes is the lesson we can learn from studying the structure of living organisms and animal and human societies.”

The Munich zoologist and neurophysiologist Gerhard Neuweiler (1935 - 2008) was Ligeti’s apartment neighbor. The two of them became friends during their stay and continued their exchanges long after the end of their common year. Something rare developed out of these talks, a scientific publication by Gerhard Neuweiler that is ultimately owed to Ligeti’s insistent queries: research inspired by an artist. The reverse – art inspired by research – is more often encountered and is demonstrated by many examples since Leonardo. In an article titled “What distinguishes human beings from primates? Motoric intelligence”, Neuweiler elucidated an idea that derived from his talks with Ligeti, which again and again circled around the question, “Why is the human brain so much more creative than that of our closest relatives, with whom we share almost all our genes?” Neuweiler’s answer was, “As a biologist who is concerned primarily with neurobiology and behavior, it was clear to me that the decisive difference between the ape and the human being did not lie where it is intuitively sought, namely in cognitive abilities, our associational power, our logic, and our curiosity, but in our motoric intelligence, which builds upon the specificities of primate motorics. … The motoric ability to speak and to manipulate, dexterity, are the two unique characteristics that give rise to cultures and civilizations and that leave our speechless relatives behind in nature and the animal kingdom.” Motoric intelligence, that is Ligeti’s and Neuweiler’s key term not only for what ultimately distinguishes human beings from primates (to the degree that it refers to the organs of speech and to fingers), but also for the neurophysiological preconditions of the production and reception of complex metrical-rhythmic structures in music. How is it possible that, in some of his etudes, a pianist like Pierre-Laurent Aimard can play in six different tempi at the same time? That had been Ligeti’s question.

Neuweiler then published a second book that documented in another way his talks with Ligeti, a summing up of his thinking about evolutionary biology and neurophysiology that spans an arc from the beginnings of organic life on our planet through the development of the human brain to cultural evolution, whose title translates roughly as “And we are it after all – the crown of evolution” (“Und wir sind es doch – die Krone der Evolution,” Wagenbach-Verlag 2008). In conversation with the artist, the biologist had learned that there is fervent curiosity about scientific research beyond the community of researchers and that one must find a language suited to it. To this end, he undertook something that only a few advanced natural scientists – at least in Germany – would trust themselves to do: to develop a generally understandable synthesis of his knowledge, thereby unavoidably simplifying matters, bringing research that is still in flux into preliminary concepts, and putting everything in an evolutionary and cultural historical perspective ultimately based loosely on Johann Gottfried Herder. Neuweiler expected his biology colleagues to pounce on this book – and they did. In effect, his exchange with the artist had given him an inner freedom and equanimity that he could not or, at least, did not get from his scientific colleagues.

What made this interchange between an artist and a natural scientist so singular was something that would exasperate every cultural politician or business manager, the kind of person who aims at rapidly presentable results and headlines: first, that here were two quite extraordinary personalities who had been talking with each other away from public podiums and television cameras, developing trust over a long period, and carrying out their exchange of ideas without any fanfare; and, second, that the actual harvest of their talks did not become immediately manifest but only appeared after several years. We can only speculate what these talks would have meant for Ligeti’s composition to texts from Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in the Wonderland” if he had had time to complete it. He wanted to write music not only to Carroll’s poetic language, but also to his mathematical texts, which probably would have turned into an intricate, complex construction in which musical und mathematical relations reflected each other in a way imbued with both wit and deeper meaning.

Ligeti announced a public evening lecture on January 24, 2001 at the Wissenschaftskolleg with a short text in the style of a statement of quasi-scientific ethics, with which he used to speak about music: “I have the tendency to change my work methods after realizing some ideas. This has a certain parallel with scientific work: as soon as a problem is solved, a wealth of new questions arises demanding new solutions. The difference between scientific and artistic work consists primarily in the absence of reality testing. In the natural sciences, an experiment must be repeatable. In the humanities there are no experiments; here, instead, there is the criterion of plausibility. In mathematics, reality plays only a subliminal role, but the desiderata of consistency and coherence apply. For the arts, the criterion of logical consistency does not apply, but a kind of coherence, or at any rate a ‘seeming coherence’, is the precondition. A polyphonic construction, for example a fugue by Bach, behaves in such a way that we have to believe ‘the music is right, just the way it is’ and could not be any different. … I do not compose ‘scientistically’; music is not mathematics, but on the other hand, mathematics can have a fecundating effect on musical ideas.”

That is Ligeti’s summary of the parallels and non-parallels between music and scientific research. Probably no other musician of his generation would have been capable of such a formulation spanning music, mathematics, the humanities, and the natural sciences. Of course, hardly any of his colleagues would have approached the process of composition as a mode of problem solving in this way.

Can one draw from this history some general conclusion about composers in residence at research institutions? With his comprehensive knowledge and his curiosity and competence in the natural sciences, Ligeti is certainly an exception among his composer colleagues, and the fact that he found in Gerhard Neuweiler a congenial, scientifically competent and artistically interested friend is equally unusual. Such summit meetings are rare, and the experience gained from them can be generalized only to a limited extent. A joint, problem-oriented cogitation like that practiced by Ligeti with Neuweiler is also something rare; even at the Wissenschaftskolleg there has been little that can be compared to it.

As differently as each case of a composer in residence at the Wissenschaftskolleg was, almost all of them soon became the fulcrum of their class. While substantive and not simply sociable communication is often difficult with specialists in obscure fields, it seems easier with the composers and is always stimulating, both for the music lovers and connoisseurs among the Fellows and for the uninitiated. Perhaps there is also another reason: while scientific thinking is charged with anxiety in many ways, and especially in the context of career, guild, and the public realm, artists provide examples of how one can confidently ignore traditions, school conventions, and custom and precisely thereby become creative. Admittedly, artistic production, too, can be highly steeped in anxiety, as can be seen especially among young artists working outside of all institutional context. Yet composers in residence at the Wissenschaftskolleg have usually seemed different: an embodiment of rigorous method with freedom from anxiety, of imagination sparked with radical innovativeness. Of course, scientists can also display such characterisitcs. Established senior scholars, in particular, often convey a habitus of freedom from anxiety and even a willingness for radical departures that they might not have taken when younger; certainly, Gerhard Neuweiler provided an example of this in the last years of his life. Interestingly, others then often perceive them as somehow artistic – or perhaps such happens because they have stylized themselves that way. Their fearlessness in relation to the standards of disciplinary knowledge, of careers, and of public opinion clothes itself in specific artistic airs.

Ligeti announced a public evening lecture on January 24, 2001 at the Wissenschaftskolleg with a short text in the style of a statement of quasi-scientific ethics, with which he used to speak about music: “I have the tendency to change my work methods after realizing some ideas. This has a certain parallel with scientific work: as soon as a problem is solved, a wealth of new questions arises demanding new solutions. The difference between scientific and artistic work consists primarily in the absence of reality testing. In the natural sciences, an experiment must be repeatable. In the humanities there are no experiments; here, instead, there is the criterion of plausibility. In mathematics, reality plays only a subliminal role, but the desiderata of consistency and coherence apply. For the arts, the criterion of logical consistency does not apply, but a kind of coherence, or at any rate a ‘seeming coherence’, is the precondition. A polyphonic construction, for example a fugue by Bach, behaves in such a way that we have to believe ‘the music is right, just the way it is’ and could not be any different. … I do not compose ‘scientistically’; music is not mathematics, but on the other hand, mathematics can have a fecundating effect on musical ideas.”

That is Ligeti’s summary of the parallels and non-parallels between music and scientific research. Probably no other musician of his generation would have been capable of such a formulation spanning music, mathematics, the humanities, and the natural sciences. Of course, hardly any of his colleagues would have approached the process of composition as a mode of problem solving in this way.

Can one draw from this history some general conclusion about composers in residence at research institutions? With his comprehensive knowledge and his curiosity and competence in the natural sciences, Ligeti is certainly an exception among his composer colleagues, and the fact that he found in Gerhard Neuweiler a congenial, scientifically competent and artistically interested friend is equally unusual. Such summit meetings are rare, and the experience gained from them can be generalized only to a limited extent. A joint, problem-oriented cogitation like that practiced by Ligeti with Neuweiler is also something rare; even at the Wissenschaftskolleg there has been little that can be compared to it.

As differently as each case of a composer in residence at the Wissenschaftskolleg was, almost all of them soon became the fulcrum of their class. While substantive and not simply sociable communication is often difficult with specialists in obscure fields, it seems easier with the composers and is always stimulating, both for the music lovers and connoisseurs among the Fellows and for the uninitiated. Perhaps there is also another reason: while scientific thinking is charged with anxiety in many ways, and especially in the context of career, guild, and the public realm, artists provide examples of how one can confidently ignore traditions, school conventions, and custom and precisely thereby become creative. Admittedly, artistic production, too, can be highly steeped in anxiety, as can be seen especially among young artists working outside of all institutional context. Yet composers in residence at the Wissenschaftskolleg have usually seemed different: an embodiment of rigorous method with freedom from anxiety, of imagination sparked with radical innovativeness. Of course, scientists can also display such characterisitcs. Established senior scholars, in particular, often convey a habitus of freedom from anxiety and even a willingness for radical departures that they might not have taken when younger; certainly, Gerhard Neuweiler provided an example of this in the last years of his life. Interestingly, others then often perceive them as somehow artistic – or perhaps such happens because they have stylized themselves that way. Their fearlessness in relation to the standards of disciplinary knowledge, of careers, and of public opinion clothes itself in specific artistic airs.