The Future of the Humboldt Forum: An Epiphany

H. Glenn Penny Fellow 2017/2018

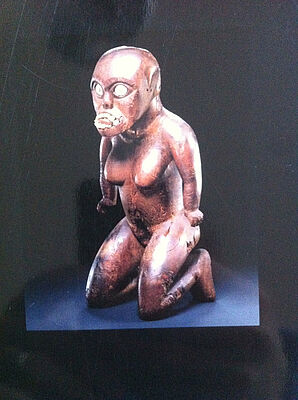

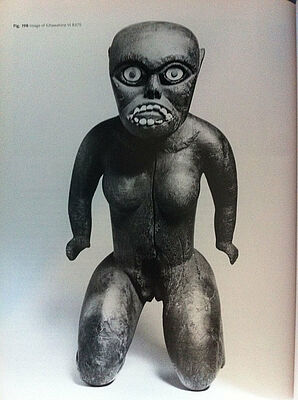

It was the skulls that caused Greg to contact me; those and the bones; and the human teeth on an unusual sculpture with strong religious resonance. Kihawahine is one of some five hundred objects the German physician Eduard Arning collected while studying leprosy in Hawai’i in the mid-1880s and which he gave to the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde upon his return. Ostensibly, Arning retrieved Kihawahine from a burial site.

Greg Johnson teaches religious studies at the University of Colorado. He has spent his career focused on American Indian and Hawaiian encounters with U.S. and international legal systems. He had traveled to Germany because the state of Saxony was poised to return Hawaiian human remains housed in Dresden to a group of cultural practitioners and repatriation experts, including Halealoha Ayau, with whom he had been working for years. This group of six was now underway to claim the remains. It was a momentous, cathartic occasion, and Greg did not want to miss it.

He and his friends also had some questions about Berlin. Its Ethnological Museum is one of the largest and most important in the world. It contains over 500,000 objects, including one of the most significant historical collections of Hawaiian artifacts outside of Hawai’i. Eduard Arning had presented his collection to the Berlin Anthropological Society during a conference at the Museum für Völkerkunde (today’s Ethnological Museum) in February 1887. It was following this lecture that Adolf Bastian, the father of German ethnology and director of the Berlin museum, lauded the “treasures” in the collection and argued that Arning’s singular gift had transformed their assorted Hawaiian items into a collection that was literally “one of a kind.” He also congratulated Arning for the precise information he had accumulated about the artifacts, explaining to the audience that Arning’s collection demonstrated what could be achieved with “serious effort, skillfully applied.” Rudolf Virchow, the eminent pathologist and founder of the Berlin Anthropological Society, similarly praised Arning during his introduction to the lecture, before noting: “We will return another time to the rich collection of skulls, which he has likewise brought us, and to the outstanding photographs of Hawaiians, which for the most part he took himself.”

I came to the Wissenschaftskolleg to finish a book focused on re-narrating German history, telling that tale by placing interconnected German communities—rather than the nation-state—at its center. Soon after I arrived, however, I was catapulted back into my own past, again assuming the role of a historian of German ethnographic museums. A series of museum directors, ethnologists and historians wanted to talk to me about the history of German ethnology, ethnographic museums and the Humboldt Forum. I initially chalked that up to the Wiko effect—many more people knew I was in Berlin than during one of my usual trips—so I politely declined most of the invitations and stayed focused on finishing my book. That all changed, however, after Greg’s call and after I met him and the others at the Berlin Ethnological Museum to help them negotiate the German language, the museum’s bureaucracy, and the structures of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz.

It was a tall order. From the perspective of someone who wrote a book on the history of German ethnographic museums during the period in which they acquired the vast majority of their collections, it is hard not to notice just how frequently participants in the last decade of debates surrounding the Humboldt Forum have misrepresented and misused the history of those collections. A conspicuous number of people on both sides of the debates seem keen to instrumentalize those collections and their history for their own purposes. Perhaps that’s why history seems to be repeating itself: a giant edifice that transforms scientific collections into a municipal display? A building deemed inadequate before its completion? Ethnologists and their efforts subordinated to the dictates of politicians and bureaucrats? Bildung usurped by Schausammlungen and edification by entertainment mixed with didactic displays? The gift shops and cafés are new; the rest, however, sounds strikingly familiar. So too does the dramatic disjuncture between funding for the municipal displays (meant to impress visitors) and monies allocated to support the museum’s staff, their research, future collecting, and the kinds of collaborative work Halealoha Ayau’s group hopes to initiate.

I’m not sure when the epiphany came. Maybe it was already there as Halealoha Ayau, who long worked with Hui Malama I Na Kupuna `O Hawai`i Nei, a leading group in indigenous repatriation worldwide, emerged with the others from the taxi ready to talk. It was an impressive group: a Hawaiian studies professor and prominent sovereignty activist, a museum studies professor, a representative of the Edith Kanaka`ole Foundation, who was the group’s lead chanter and ritual protocol expert, and Kamana`opono Crabbe, CEO of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, which supported the trip. But maybe it was the earnestness with which they looked at the books on the shelves of the curator’s office where we met to talk about the collections. It might have been the way in which the group drew us together around the table after drinking coffee, stood up, had us clasp hands, and burst into a chant that lasted longer than the uninitiated could imagine possible. It might have been the seriousness with which Halealoha Ayau questioned the curator about the collections, the locations of objects and body parts, and the reasons for Arning’s collecting practices. Perhaps it was because the curator was so forthcoming, so eager to work with them, making sure that even those objects which they identified at the last minute could still be viewed. She never questioned the fact that the lead chanter, after ascertaining which objects would be seen, repeatedly left the room to make international calls to older family members in order to determine which chants and procedures were necessary for initiating their relationships with the objects. There is no question that I felt lucky to have the chance to see them present the curator with a different ontology, to explain the ways in which they related to and communicated with the remains and other culturally significant objects. But it was more than that. During this meeting I saw the future, the way out of the conundrum that is the Humboldt Forum. Working relations like these are the future of German ethnological museums, and the best relations require openness to cultural difference as well as a keen understanding of the history of the collections.

I did not expect to return to the history of ethnology and ethnological museums when I arrived in Berlin in September 2017. Yet opportunity did not simply knock on my door; it pushed it open, tore me out of bed, and then shook me until I realized: That was what I was meant to be doing here.