Issue 14 / June 2019

The Data of Dating

Stefan Klein

Sociologist Elizabeth Bruch researches online dating behavior with the goal to better understand how humans make decisions

Stefan Klein: Ms. Bruch, you are researching online dating. When did you first learn about such platforms?

Elizabeth Bruch: My sister introduced me to the Internet exchanges. That was one weekend in 2002, when I lived in Los Angeles. At that time online dating was still considered exotic.

SK: Today every third American between the age of 18 and 29 uses these portals.

EB: By now it’s become perfectly normal to find your partner on the Internet. Back then we were curious and spent some time investigating this new world. But in fact I did find someone who interested me. He was a budding filmmaker and lived in a part of town that was very different from my own surroundings. So I wrote a profile and then sent him a message.

SK: What happened?

EB: We were together for two years. But my approach was atypical.

SK: Because you’d only set your cap at one particular man?

EB: That’s it. Most people go to dating sites to make contact with as many candidates as possible.

SK: In competition with thousands of other women, you had to somehow attract his attention.

EB: I don’t know how I did it. I knew way too little about him to make up a particular story. That’s the problem: The guidebooks are full of tips on how to write supposedly irresistible profiles. For example, one dating site suggests that adding certain words to your profile, including “perceptive” or “affectionate,” increases your chance of getting a response. One dating expert suggests that you always include an “icebreaker” question. But all these supposedly sure-fire strategies are based on weak empirical evidence. In reality, people act without knowing whether what they are doing will pay off. We have found, for example, that the more attractive a man is, the longer are the messages which women will post on dating portals.

SK: Understandably. They hope they can increase his interest by saying more about themselves.

EB: But they’re wrong. Whether and how the men answer does not depend on how many words they say. The women are just wasting their time. By the way, the men do it more skillfully. Sadly, gentlemen succeed when they play it cool. It’s no use giving compliments to an attractive woman.

SK: What is an attractive person?

EB: We define attractiveness based on how the users of the dating portal respond to one another. We evaluate who gets messages from whom. The more messages a recipient receives and the more attractive the senders are, the more attractive the person is. The most popular person in our record, a 30-year-old New Yorker, was courted by someone every half hour. Most partner seekers, on the other hand, received one or two requests per month. Because of the de-identified data, we don’t know what it is about this person that makes them so unique.

SK: You use the word “record.” What does that mean?

EB: We have data for an American online dating exchange from 2014. Four million active users.

SK: Where did you get this data?

EB: We acquired it from the company. All the information is, of course, anonymous. And we have taken special security precautions so that only designated scientists can access it.

SK: Apparently you know the age, sex, ethnic background and education of all these people as well as the city they live in. And you know what was written between them. Are outsiders allowed to experience such intimacies?

EB: No, the data is not publicly accessible. Researchers who work with this type of data also have to go through an ethics review at their home universities, which provides an additional layer of protection.

SK: Still, if I had posted on this dating page back then, I would feel like someone was paging through my youthful diary without my permission.

EB: We may be still in the early phases. But we are figuring out how to use this data responsibly and in ways that protect the individuals who contribute it.

SK: That sounds similar to the replies Mark Zuckerberg offers when being accused of mishandling his users’ data.

EB: Well, but as a scholar I work by the National Research Act of 1974, which laid out a set of ethical principles for conducting research, known as the Belmont Principles. These are specific guidelines that allow us to collect information in a manner which respects and even benefits those concerned. We can follow similar principles on the Internet. We need partnerships between entrepreneurs, scientists and the government.

SK: Not only social networks, which also include dating devices, follow us every step of the way. GPS and radio networks record when and where we move. Streaming services know our taste in movies and music, Amazon knows what we’re buying. The companies expect more turnover from it. What do you as a scientist want to do with all this information?

EB: Big Data opens up new ways to understand our behavior. I believe that these types of data have a great deal of insight into how we go about our decisions, and that information can be used to improve people’s lives. An example: If we want to investigate a link between insomnia and obesity, so far we have had to rely on surveys. But the surveys do not reveal how those affected go to the fridge at midnight and snack. Understanding decisions on this micro-level may be critical in developing better programs to combat obesity.

SK: A mobile-phone microphone, a refrigerator connected to the Internet or a smart speaker like Amazon Alexa would disclose such behavior – at the price of total surveillance.

EB: I agree that we need to be very careful with how we collect such data. It is also important to educate users so that they can make informed decisions about how to manage their privacy settings and understand the implications of using a particular app or device.

SK: I am not sure if what you suggest is sufficient to protect users. But I agree that transparency is crucial. Everyone has the right to know in detail what happens to their data. What exactly do you want to find out with your research?

EB: I want to fundamentally understand how people make their decisions and then use that information to improve people’s lives. My interest has a long history. I came to sociology when, after finishing high school, I went to a Romanian orphanage for an aid organization. That was 1992. The conditions were terrible. The children lived in rooms that looked like kennels. I was told that the mortality rate was 50 percent, there was a graveyard on the premises. So we built the donated playground, but we knew how inadequate our efforts were. The misery had fundamental causes. I wanted to help tackle them.

SK: You studied sociology because you hoped to change the world.

EB: Yes. Before I researched online dating, I studied poverty and the division of social classes into neighborhoods. For this purpose I developed statistical models ...

SK: ... mathematical formulas for the probability that a person will do something specific. If you had those, for example, you would know more precisely why certain population groups move to certain areas.

EB: Or how it happens that so many overweight people live in some neighborhoods. Why do people in these areas have such an unhealthy diet? Ultimately, it has to do with what they put in their shopping basket at the supermarket. So we have to find out what causes a particular behavior at a particular moment.

SK: But when do I know which certain monkey is on my back when I carefully circumnavigate the fruit shelf to zero in on the XXL bags of potato chips?

EB: Exactly, many drives are unconscious. However, today’s marketing teams know an astonishing amount about what our decisions depend on, since they use motion detectors to track customers’ paths, eye sensors to measure their gaze, and payback cards to know the buying habits of millions. Marketing is fascinating. But what is known there should actually be used to solve the problems of society. Is it really because of the price, for example, when people on low incomes eat too few vegetables? Rather there is much to suggest that many of those affected are single parents, have several jobs and are therefore specifically looking for ready meals that they can prepare quickly. Effective measures can only be taken if we understand such interrelationships.

SK: Why don’t you just adopt the findings from marketing?

EB: Because choosing yogurt is different from choosing an apartment or choosing a partner. Yogurt won’t buy you back. Most life decisions, on the other hand, are two-sided: the other side must also want you. That is why these decisions are made much more strategically. Data from dating portals is perfect for understanding just what happens in such situations.

SK: What have you learned from your data on the strategies of love?

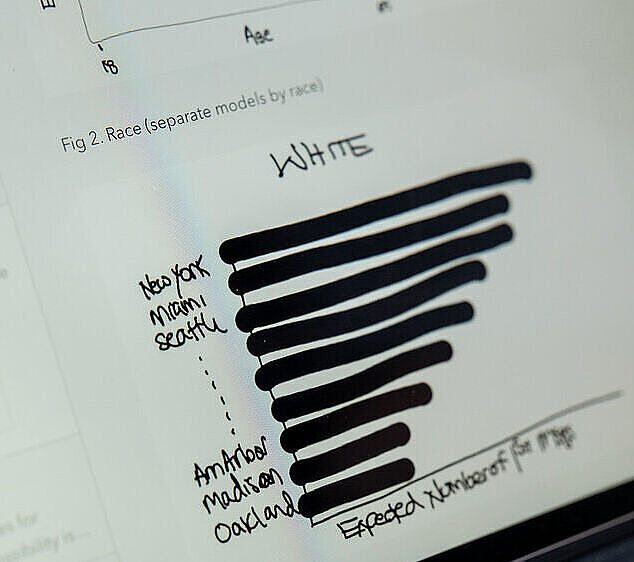

EB: People are oriented upwards. They seek contact with others who are on average 25 percent more attractive than themselves. Women are more attractive to men the younger they are. Conversely, women hardly look at the age of men at all, but they want the highest possible level of educational attainment from their future counterparts.

SK: A doctorate is an advantage.

EB: Absolutely. But only in men. Men on the other hand are largely indifferent to the educational background of their partners. The most attractive women, on average, only have a single university degree.

SK: Women desire status, men beautiful bodies: you seem to confirm the tritest of clichés.

EB: I was also shocked when I first saw the evaluations. But what I just said is only true on average. Not all 4 million partner seekers follow the statistical norm. I would now like to know what distinguishes people who behave differently. These are the characteristics we’re looking for right now. The search strategies are also informative. On the portal, the user can set which properties he or she finds so unattractive that the computer should not even show corresponding candidates. Women very often filter out men without high school graduation, men filter out women who are older than themselves.

SK: The dating portal you are looking at is aimed at people who don’t want a brief fling but a lasting relationship?

EB: Yes.

SK: Then in that case the singles are behaving very strangely. How do the men know that they will be happier with a 20-year-old than with a woman who is a little older than themselves but whose profile they don’t even want to look at? And why are the female lonely hearts so sure that they are most likely to find a man who suits them among those with university degrees?

EB: The search strategy is perhaps not entirely rational. It’s based on certain beliefs and limited experience. And that’s how we make many life choices. We choose badly because we do not have enough information to know what is good for us.

SK: They thus deny a central dogma on which our social order and our economy are based: Every individual should be given as much freedom of choice as possible because nobody knows your own needs as thoroughly as you yourself.

EB: We know that’s not true. If the behavioral research of the last twenty years has shown one thing, it is how fallible our decisions are. For example, it is very easy to manipulate preferences by putting them into a certain context. Just go to a department store. There you get to see outwardly similar jackets for 300 euros, one for 500 and one for 5000 euros. What do you buy? Most people opt for the average offer of around 500 euros. They don’t know that a 5000 euro jacket is only in the assortment so that they won’t choose the cheapest garment. And it works! There is a whole literature about such effects.

SK: John Stuart Mill, one of the pioneer thinkers of the market economy in the nineteenth century, actually knew this. He argued that people are only able to shrewdly assess their daily basic needs. But the more rarely we make a choice, and the more it affects our own character, the harder it is for us to act in a way that will ultimately benefit us.

EB: That’s right. And what is your guess: How many candidates do singles looking for a relationship typically meet in the course of a year?

SK: Probably depends on how picky they are – a dozen maybe.

EB: No. Three. And how often do we even choose a partner in life? Or a profession?

SK: The more far-reaching a decision, the less opportunity we have to gain the experience we would need to make good decisions. Probably our individualistic culture overwhelms us when it expects us to determine our own lives by making all the correct choices.

EB: That’s right.

SK: Traditional societies make it easier for their members. It’s the family that decides which job to take and who gets married. And then the individual simply has to come to terms with what others have chosen for him or her.

EB: I come from a Jewish family. My aunt is a matchmaker. She happily married some of my cousins in her New York community. But the success of these marriages also stems from the fact that the families in the congregation are similar and get along well with each other.

SK: How does your aunt choose the right one for someone?

EB: She keeps the candidates in a file. I never asked her what strategy she used to take her decisions. But I’m sure she does have one. Factors such as family fit are likely to play an important role. I believe that our happiness depends less on whether our individual wishes come true than we think it does. Conversely, we underestimate how strongly the environment influences our well-being.

SK: But even if we choose our partner online according to our wish list, we are still encouraged to underestimate these environmental influences.

EB: Yeah, but it doesn’t have to be that way. I can imagine an algorithm that involves the social environment when proposing a companion.

SK: A computer that works like your aunt does ...

EB: ... but which does not select candidates from a single Jewish neighborhood. The world offline is very small, online infinitely bigger.

SK: But for the machine to find the right one for me, I would need to not only know a lot about myself but also my family and friends. Ideally, it would also be able to predict how I will develop over the next few decades.

EB: Certainly. Today’s programs are still at the very beginning of their development. We must finally understand that algorithms are not a crystal ball or gift from god. They are trained on data that is provided by humans, based on previous experiences, and as such can replicate or even amplify human fallibilities or biases. Thus we certainly should not blindly make our decisions based on their suggestions. However, algorithms might be good for giving us suggestions for things we wouldn’t normally consider.

SK: I’m supposed to give everything they can find out about me to a computer: personality profiles, knowledge of my social relationships, even my genome. I’d also have to reveal my sexual preferences. In return, I am promised the best possible partner. Would you make this deal?

EB: If I was sure that firstly the algorithm would work reliably and secondly there was a structure in place that ensured that the data was collected and analyzed in transparent ways – then yes. How about you?

SK: I would give it a try – but only if at some point the two conditions you mentioned apply. Whether it ever comes to that, I doubt it. If the Internet continues to develop as it has in the last two decades, the manipulation and misuse of intimate information will even increase.

EB: I’m more optimistic.

SK: I hope you’re right. But I do understand that many of our contemporaries are horrified at the notion of creating love by means of a computer, even under such ideal conditions.

EB: Why?

SK: Because it means admitting that I myself don’t best know what’s good for me. My desires must take a backseat – for my happiness I will be giving over control of my life to a machine.

EB: But in that way you simply acknowledge reality! Often reality is too complex for our minds. Perhaps we can come to terms with it more easily if we feel that we’d be better off by letting ourselves be helped. And don’t forget, you won’t give up your autonomy! No one can force you to marry the woman or take the profession that the computer has chosen for you.

SK: I’d be skeptical about that too. The better we understand our behavior through Big Data, the better the recommendations we get, the greater the pressure to act accordingly. And who wants to voluntarily be led astray? We lose the freedom to make mistakes.

EB: You are right. Perhaps we should integrate random generators into the algorithms. Occasionally the computer would then recommend completely crazy things to us.

More on: Elizabeth E. Bruch

Images: © Maurice Weiss