Issue 14 / May 2019

“Everyone can learn to theorize better!”

Hans-Joachim Neubauer

Richard Swedberg talks about theorizing, Charles Sanders Peirce, and the need to get up on the theory bike

Hans-Joachim Neubauer: What is a theory?

Richard Swedberg: In philosophy of science they might tell you that a theory is something like an interrelated set of propositions that can be tested, something dry like that. But in reality a theory is much more than that. It is also the result of a very interesting physical and mental process that is full of mistakes, false leads and happy accidents. There is a big difference between the final formal theory and the making of that theory. Theorizing basically refers to the process of making a theory.

HJN: Theorizing seems to be the adventurous part of a theory.

RS: I am basically interested in what happens at an intermediary level, at the level that exists between the empirical facts and existing theories – the part where you make the theory. In philosophy of science there is a famous distinction between the context of discovery and the context of justification. The context of discovery is when you unearth or ascertain something, the context of justification is how you present what you have discovered to your peers in the scientific community. When you do the latter you have to be very logical and clear; you have to describe your methods and facts, etc. But that’s just the final element in a long process that starts with something else: theorizing.

HJN: What you call theory doesn’t sound very entertaining.

RS: Well, at least to me most of the fun and the really interesting stuff happens before you have finished a theory and have it up and running. But the point of theorizing is of course to produce a good theory; and theory and theorizing complement one another.

HJN: I still have a sense that you think that theory is a bit dull …

RS: You are right. And one important reason is that today’s theory is not very well developed. We don’t know very much. The great fun would be to unlock a bit of the great mystery of what it is that makes people think in the first place. Human beings are basically born with a capacity to create theories, to theorize. All human beings theorize, it’s a general human capacity.

HJN: So we are born theorists?

RS: Yes. To theorize is a biological capacity. But it is also true that it is a capacity that can be developed to some extent, and especially under favorable social circumstances. Just as it can be blocked and prevented from flourishing.

HJN: What does this biological capacity include?

RS: It entails such things as being able to create and use concepts, to think in terms of explanations, categories, abstractions and more. All of this is what you use when you’re creating a theory.

HJN: When you teach, do you focus on theory or theorizing?

RS: Both, but mainly on theorizing. When students take theory courses in my field, which is sociology, they read texts by people like Marx, Weber and Durkheim – but that does not teach them how to create a theory or add to some existing theory. Most have a fear of theory – Theorieangst! – and this fear is quite natural because here they are, and what you give them are works by Marx, Weber and Durkheim, all of whom are clearly these giants of thought.

HJN: So everybody has to fight against the giants?

RS: Well, those giants spent years developing their theories, and the students have spent perhaps three weeks in a theory course. So we know how the fight will end. It’s like a professional boxer versus a young amateur: Even if you are a good and talented amateur you will get knocked out by a lousy professional in two seconds.

HJN: So what do you do to make your students learn theorizing?

RS: The first thing I do is to try and make them lose that Theorieangst. To make them understand that there is no point in trying to replicate what Marx and Weber have already said. They are alive, while the classics are dead; and it is always preferable to be alive. Every person is the center of the world, and that also goes for theorizing. So learn to think for yourself or someone else will do it for you, as Kant said, don’t be unmündig! There is also the fact that by virtue of being a human every person has been given the capacity to create theories. So train that capacity and see how far you can go. There is a lot of creativity locked away in the students. I would like to pull it out, so that sociology can once again become an exciting science!

HJN: Is it boring now?

RS: It was very exciting in the days of Weber, Simmel and Durkheim, but it is definitely less so today. Some excitement is needed today, and I think that theorizing is one of the most important things that can bring it back – and take sociology into the twenty-first century.

HJN: Did you yourself have good teachers when you were a university student?

RS: Unfortunately not. I would have loved to have had great teachers. But I also realize that by not having great teachers I had to sort of create myself. After I got my PhD I took courses with Noam Chomsky and some other really great people. I was living in Cambridge at the time and Chomsky was teaching at MIT. So I just walked into his classroom, listened and learned. He introduced me to Peirce and so much more. Charles Sanders Peirce and Noam Chomsky are my two big intellectual heroes.

HJN: Heroes can be dangerous.

RS: That’s true. Some thinkers like Foucault and Weber are so attractive – and so dangerous. I call it the Bermuda Triangle. Go there and you will never get out. These type of thinkers have a fascination for many of us, like the proverbial pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. You will never find it but you also can’t stop thinking about it. People like Foucault and Weber seem to have the answer to all those hard and interesting questions you are thinking about; and to find out what those answers are, you only have to study their works a bit more. But I’ve learned through experience that you should try to keep these powerful thinkers at a bit of a distance. You need to first think for yourself; then you can read what the big thinkers say.

HJN: But you need good theories to make good science, don’t you?

RS: Sure, and that means reading and studying existing theory. But there is a big difference between reproducing what someone says and using their work to create something of your own. You know what they say: bad poets imitate, good poets steal. So that’s where theorizing comes into the picture.

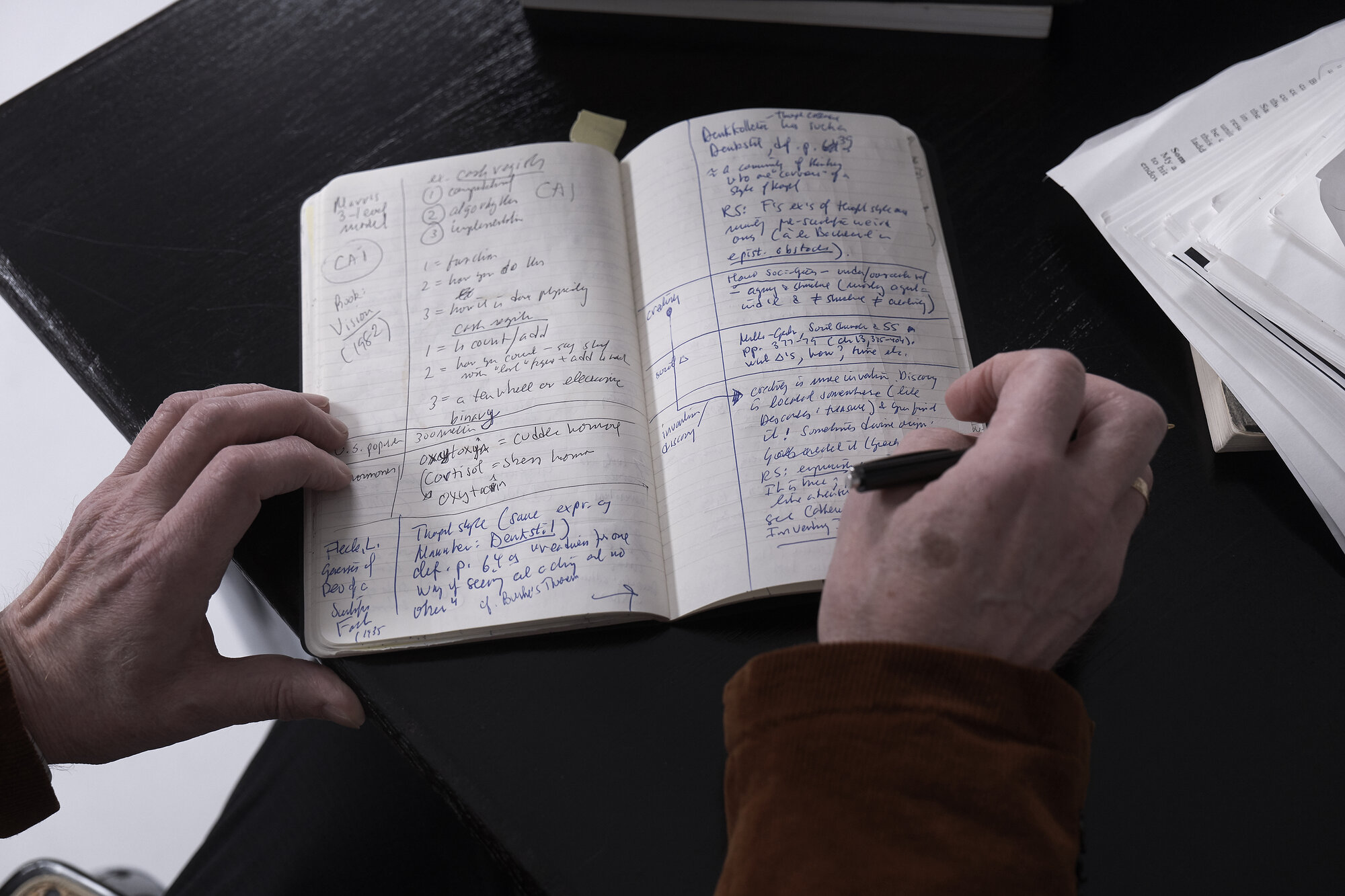

HJN: Besides producing a good theory at the end of the process – what is involved in theorizing?

RS: It's a kind of practice. It’s a doing. Theorizing is a verb; theory is a noun. Theorizing can be described as a special form of mental activity; it’s also something you can train yourself in. Like the people in the pragmatist tradition – Peirce, James, Dewey and so on – I put a lot of emphasis on habits. You need to become good in theorizing – and then turn what’s good into a habit. We can all learn to theorize better!

HJN: Since theorizing is so creative – where would you draw the line between this type of practice and the practice of, let’s say, writing poems?

RS: They are two very different activities. The purpose of theorizing is to produce a good explanation, not good literature. But there is also some overlap. I have had my students read poems as part of learning how to theorize. They learn, for example, how to make associations from studying the way poets use words. And you always get inspiration from studying something creative.

HJN: When will you write that big book on the propaedeutics of theorizing?

RS: Oh, I’m not good enough for that kind of thing. I don’t have the brainpower of a great thinker. I am happy to work in my own little garden.

HJN: Is learning to theorize like learning to drive a car?

RS: Super talented people create good theories more or less automatically or intuitively. But we mortals must learn how to do it. And in the beginning, as when you learn how to drive a car, you have to start with the simplest and smallest of things. How do I signal that I am turning and the like? And after some training in what induction-deduction-abduction are all about, you can forget about them; they have now turned into a habit. You are now able to drive more or less automatically.

HJN: How do you interpret Charles Sanders Peirce’s complex concept of abduction?

RS: He describes it as a biologically based, evolutionarily developed capacity of human beings to create something new, by a leap of mental imagination. The new idea, he also says, is usually incorrect. And it always has to be tested. But it is much more often correct than it would be if it were just randomly generated; and that’s the key point.

HJN: The whole thing sounds easy: Just a leap of mind and you have produced something very creative?

RS: Well, those mental leaps and imaginations are not simply coming to you. What Peirce is also saying is that in order to have those leaps of mind you have to work hard. Very, very hard. You have to create the data, look at the data, look again at the data, sleep on top of the data, dream about the data. And not to forget: ideas come when they want, not when you want them to come, as Weber says.

HJN: So induction and deduction are not novel ideas.

RS: Well, according to Peirce, novel ideas only come through abduction, not through induction or deduction. The capacity to develop new ideas is biologically based, but you can also help things along a bit, apart from all that hard work. Peirce advised people to lift weights – that helps you to face the task of doing heavy mental labor. And also to take walks, at dusk or dawn, that helps to loosen up your mind. Presumably Peirce did all of this himself. He also lived in the countryside, in Milford, Pennsylvania, and was quite eccentric. You should read Joseph Brent’s biography of Peirce – it’s a wonderful book. Very abductive!

HJN: Is a new idea something you feel – or something you think?

RS: When people emphasize cognitive factors they typically focus on the part of their thinking that they are conscious of. And what people are conscious of is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to thinking. If you want to explain what generates thinking you need to look at the whole iceberg; and no one knows what that looks like. Peirce’s way of dealing with this is to look at what is on the borderline between what we are aware of and what we are unaware of. You can bring some of this into consciousness and use it for your own purposes. But the rest is a big mystery. The brain is made up of something like a hundred billion neurons that we know little about. And the brain is not the only place in the body with neurons, there is also …

HJN: The stomach?

RS: Yes. Our gut feelings are emotions or something like unconscious ideas or signals. When the gut neurons get stirred up they send diffuse signals to the person that there is something wrong. They are part of your subconscious – that area of your mind you are in touch with when you’re half asleep, dreaming, jetlagged or haven’t slept for forty hours.

HJN: And when you are taking walks in Pennsylvania?

RS: Yes. Jean-Jacques Rousseau used to take walks in the forest to get ideas. He said that his head only moved when his legs moved. He had another technique to get ideas: He would row out onto a lake and then he lie on his back and let the boat drift.

HJN: Walking, drifting – and then returning home with a new theory?

RS: Yes, if you are lucky. Things don’t usually turn out the way you want when you do research, unless you know from the beginning what you are going to find. In which case you don’t need to do any research in the first place. You basically have to work and work and throw away what you have done and start all over again. And then – maybe – you have something of value. Who knows? Until you are there, you won’t know what is there.

HJN: How do you know that an idea is good?

RS: Peirce doesn’t give a number but he seems to think that for every hundred ideas you have, maybe one or two will be good ones. Most of our ideas are useless. And you have to be able to somehow single out the good ones and avoid the deadbeat ones.

HJN: And how do you know if an idea is good or not?

RS: That’s a problem. Some say that when you have a good idea it is like a light bulb that suddenly goes on ...

HJN: Like Gyro Gearloose and his Little Helper?

RS: Exactly. Unfortunately it doesn’t work like that. It’s more like you get a small idea and then you work with it for a long time, filling it out and fattening it up. You have to first test the idea in your mind: Is it a good idea or not? Can I apply it to this or that situation? Is it too narrow? Does it open up new insights? A good idea opens things up – with a bad idea you will soon walk smack into a wall.

HJN: Do you think that Michael Polanyi’s “tacit knowledge” is involved in theorizing, given that a part of our knowledge is unknown to us because we didn’t learn it consciously?

RS: You are typically unaware of what you are doing when you theorize, so in this sense you are drawing on tacit knowledge. I myself don’t talk so much about tacit knowledge – I prefer to draw a distinction between practical knowledge and science. The former is knowing how and the latter knowing that. This distinction comes from Gilbert Ryle. You know that Paris is the capital of France, whereas you know how to use something.

HJN: So you just have to know how to theorize?

RS: What you need when you theorize is often practical knowledge, not so much scientific knowledge about the way, say, the brain works. You need to know how to ride a bike, not to know why it is that you don’t fall off the bike in a curve when you lean into that curve. You can probably explain scientifically what’s going on when you go through a curve. But I’m not so interested in that, I am more interested in how you get up on the bike and ride it. Yes, that’s it: How do you get up on the theory bike and theorize!

More on: Richard Swedberg

Images: © Maurice Weiss