Issue 18 / March 2023

We Can Do Better

by Manuela Lenzen

Biologist and metascientist Rose O’Dea is currently a Fellow of the College for Life Sciences at the Wissenschaftskolleg – and she casts doubt on our scientific system

Animals too have personalities – animals such as zebrafish. This cyprinid is native only to the Ganges River basin but its luminous stripes make this a popular fish with aquariums worldwide. If you take a closer look at a school of them, you will find both brave and timid specimens, precocious ones and late bloomers. One explanation for such “animal personalities” was examined by the biologist Rose O’Dea in her doctoral dissertation. Called pace-of-life syndrome, the idea is that more daring behaviours evolved in individuals with faster metabolisms, to compensate for their shorter lifespans. But O’Dea couldn’t confirm or refute that idea for the zebrafish. “Our findings showed nothing,” says the Australian scientist who works at the University of Melbourne and is currently a Fellow of the College for Life Sciences at the Wissenschaftskolleg.

Other studies had also failed to confirm the “live fast, die young” idea, and this was a respectable result for a doctoral thesis. Using her dissertation as a springboard, O’Dea could have launched a very promising career in behavioral ecology; yet she didn’t. “At first I thought that’s how science works – the hypothesis is being falsified. But that was wrong because the idea wasn’t well enough developed to be tested empirically. It was a loose conceptual framework, not a formalised theory.”

The young biologist gazes pensively through the large windows at the wintry black lake abutting the Wissenschaftskolleg. Two swans glide across the surface; a number of ducks and coots are also to be seen. “Without testable theories you can publish many papers, but they are meaningless, orbiting around their subject but never touching ground. Instead, at the conclusion of each paper, you just end up saying that more research is needed. After measuring all those fish, I felt so unwise and unsure of what was interesting and testable in my research field.”

She clairvoyantly prefaced her dissertation with words from the science-fiction writer Douglas Adams: “It was hard to avoid the feeling that somebody, somewhere, was missing the point. I couldn’t even be sure it wasn’t me.” O’Dea is still searching for that missing point and trying to forge her own path in an academic world that she regards with wariness – and forging that path in the same dauntless fashion as when, before her academic career, she spent four years as a professional umpire in the Australian Football League (Australian rules football), only the third woman to do so.

After earning her doctorate, Rose O’Dea left labwork behind for the fledgling discipline of metascience, a subject she’d long been drawn to. “My early supervisors were interested in understanding and improving how science is done.” For instance her doctoral advisor took her to a workshop hosted by the Center for Open Science. “That was 2015,” she recalls. “The Center had just published this important paper called ‘Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science.’” Led by the social psychologist Brian Nosek, 270 scientists from 125 institutions attempted to replicate more than a hundred psychological experiments and succeeded in only 39 percent of cases. The so-called replication crisis made a great stir at the time.

Much has changed since then. Ever more journals insist that the data on which studies are based should also be published, and openness and transparency have become priorities at least officially. Yet Rose O’Dea remains unconvinced that transparency is the essential point, citing evidence that free accessibility of data in ecology has not led to more studies being withdrawn because they proved to be unreproducible. “I worry that transparency is mistaken as a signal of reliability. Being transparent doesn’t mean that what you did is any good. It just allows others to evaluate what you did, provided that they have enough motivation and expertise to do so.” But the work of error detection and correction is not glamorous. “In fact the scientific system still bestows most of its rewards on original work,” O’Dea states. “And the more of that work the better. But it’s work whose content is often of little interest to anyone.” Funding for replication studies is difficult to attain. “But it’s not just the money; you don’t make a lot of friends with replication studies. When someone points out the errors or irregularities of others, it’s like ‘go out and get some ideas of your own! Why not just do your own thing instead of defaming colleagues?’”

O’Dea was able to spend a year writing her dissertation in Canada where she also found time for reflection. “It was a bit like being at the Wissenschaftskolleg. Otherwise, as a doctoral student, you can become narrowly focussed on lab work.” And during that Canadian year she drew a radical conclusion: No one looks at the data because no one’s really interested. “Obviously these results are completely unimportant, otherwise someone would pay attention, no?”

She meanwhile regards as naive the notion that in science everyone works together to build the edifice of knowledge, carefully laying brick upon brick. “Science is great; we certainly see that by how quickly vaccines were developed in the pandemic. I just want to emphasize that we can do better. We think we’re all little cogs in a big machine, but we’re not, we’re not connected at all, that one big machine doesn’t exist.” In fact, she says, with all the pressure to publish, researchers hardly notice each other’s work anymore. “One professor told me that when he gets applications he only pays attention to the names of the journals where someone publishes. He doesn’t even read the titles of the papers, let alone the abstracts. That’s crazy! Why do we even do the work? Think of all the time and resources that are wasted.”

She says that among young researchers, in particular, dissatisfaction with the existing system is now high. “Many leave the university sector because they’re unhappy with current incentives for career advancement.” She says there is already an essay genre called “quit lit” in which researchers share why they have turned their backs on academia. “The problem is leaving will only change the scientific system if institutions sorely miss the people who left. But there are plenty of individuals waiting to fill vacant positions.” Perhaps metascience actually makes things worse. “If you call people’s attention to grievances without improving anything, then the likelihood that they’ll leave increases.”

Improving research is the throughline of Rose O’Dea’s recent work, which is now based in an interdisciplinary metascience research group at the University of Melbourne. She created a practical guide for quantifying individual differences in the animal kingdom; she took a checklist for good scientific practice that was developed for medicine and she adapted it to evolutionary research and ecology; in 2020, together with colleagues, she founded the Society for Open, Reliable, and Transparent Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (SORTEE) and next year will become its president; and she advocates for journals to offer Registered Reports, where peer review occurs before projects start: “Studies would have to be evaluated according to their design and the quality of their theoretical rationale, and their results would then be published no matter the outcome. In that way you can avoid publication bias against negative or ambiguous results.”

All the guidelines, checklists and other specifications that have been formulated in an effort to improve research are regarded by some of her colleagues as patronizing. “They say you can’t standardize innovative research,” explains O’Dea. “I was taught because we can’t know beforehand what research will be important, we need all we can get. Now I’m unconvinced by that argument. I think that often you can already see that something won’t yield all that much. And somehow, with limited resources, we have to decide who gets them.”

At the Wissenschaftskolleg, Rose O’Dea is looking into how to evaluate evidence in ecology and evolutionary biology, where exact replications are often impossible. Instead the same thesis can be tested with other methods, in other places, or with other species. “But then if you get different results, what to do with them? Here it’s very important to determine how general a given phenomeon is.” O’Dea is trying to understand just how common such conceptual replication studies are in ecology and evolutionary research, and how best to assess the range of research results.

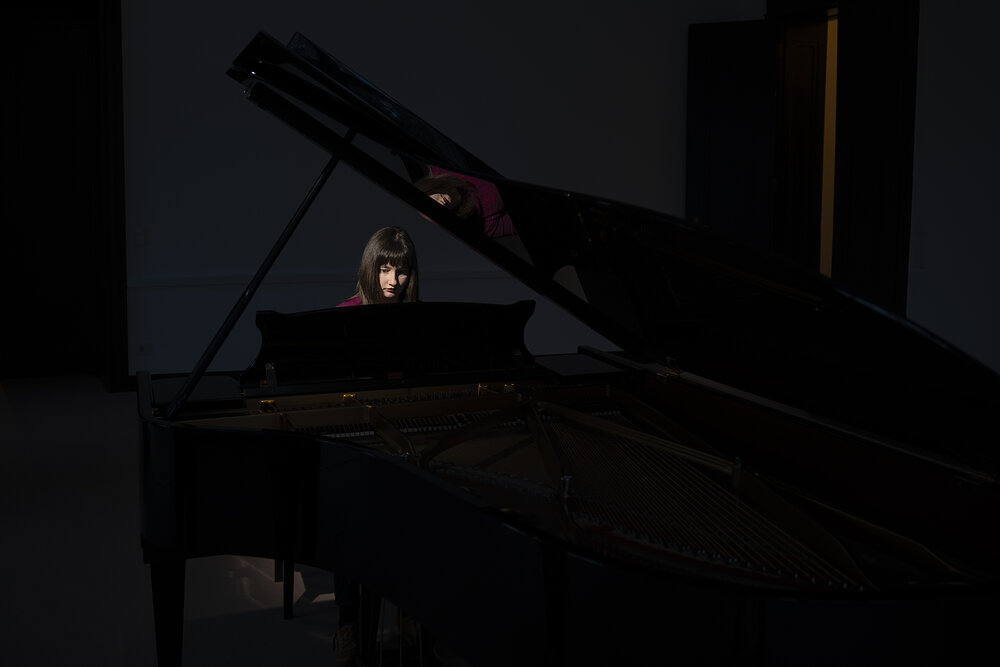

It’s admittedly a big project for just the six months she’s spending in Berlin, concedes O’Dea, who likes to sit down at Wiko’s grand piano in the Large Seminar Room on quiet evenings and get in a bit of practice. But she also uses her time to ask the other Fellows about their experiences: “It’s really exciting to talk to people and experienced researchers again after being isolated in the pandemic. And I think I’m pretty good at getting others to talk about themselves, so I learn a lot.”

This is her second time in Germany; a few years ago, she visited friends in Dresden by way of Canada. “I thought, why not, since I was already in the neighborhood.” She’s amused by so many countries in such a small area – a flight of two hours and you’re in Montpellier: “In a completely different country and they didn’t even want to see my passport!” In Germany she’s surprised at there being no water fountains in the streets and no free water in restaurants. “Everywhere in Australia they have to provide you with water free of charge.”

In exchange for time to reflect and do research in the Grunewald, she accepts the fact that she’ll miss this year’s summer; come spring she’s heading back for the Australian autumn. Time for reflection, however, can pose more questions than it answers. “I came here with a vague intention of figuring out what to do with my life, but now I realize it will always be a work in progress,” muses O’Dea. She has already completed an internship with a government agency to see what a life outside of science might feel like, and she’s presently surveying the job market for “ethically responsible jobs in data science.” She adds: “I do want to help increase humanity’s store of knowledge. But most of all I want to do something that matters.” If Rose O’Dea finally decides to pursue another career, it will certainly matter to the scientific community.

More on: Rose O'Dea

Images: © Maurice Weiss