Issue 9 / February 2014

A Reasonable Level of Bourgeoisness. Wolf Lepenies, Europe, and the Mediterranean

by Gunter Hofmann

Strictly speaking, the story began with the French Saint-Simonians, they developed a vision of how things might materialize with the Mediterranean and Europe, this recorded in an 1814 memorandum which was still full of sympathy for those lands constituting “Germany” at the time. These men were pragmatists – engineers, bankers, industrialists – and they didn’t employ grandiose European rhetoric but “dreamed” of railroads and canals, of a system that would link up Europe in a practical fashion, and all of it faithfully financed by Baron Rothschild. Although European unification would appear to be a “project of the North,” adds Wolf Lepenies to the above facts, one would do well to bear in mind that in truth much of it was “anticipated in the South” – even if they were ultimately unable to implement it. This constitutes a daunting psychological problem for those to whom we owe our thanks for having originally conceived the whole idea.

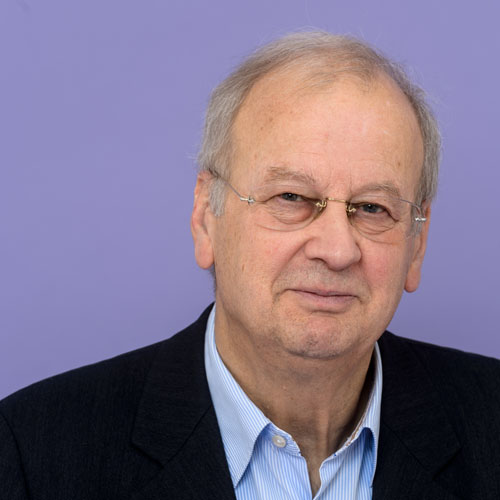

That’s how it was – that’s how it always is – you’ve hardly taken your seat with this former Rector (1986-2001) and now Permanent Fellow of the Wissenschaftskolleg in his office near the main building of the Kolleg then you’ve arrived at the crux of the matter. Here is a man concerned with the key question regarding that new Europe where the North-South conflict has been displaced by the East-West conflict, which has led to a new dispute regarding the EU’s cardinal direction – while at the same time his being concerned with a very specific approach to it. The dominance of the North, the searching movements in the South – Lepenies blithely juxtaposes conceptual and other elements to create his historical mosaic – and of course François Mitterrand plays a role, seeking to speak for the socialists from southern Europe, from the Mediterranean area (his socialisme du cœur versus a socialisme de raison), but who also got along famously with the Scandinavian-socialized Willy Brandt! Or Fernand Braudel’s monumental work The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philipp II, which Wolf Lepenies is using as supporting testimony for what in fact both divides and unites Europe. This sociologist by training, university professor since 1971, directeur d’études associé at the Maison des sciences de l’homme, and former member of the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton – this versatile scholar has found a very individual format, his format, recalling with irony those days “when I was still a real sociologist,” but withdrawing from the theoretical and methodological debates of his discipline very early on, and today prefering the simple title of “author.” That hits the nail on the head. One takes his texts to hand – essays on such topics as the Mediterranean from the African point of view, or the French Leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon, or hefty biographies on Sainte-Beuve and Auguste Comte, all these outlandish anti-heros – and one is taken by the very personal voice that shines through Lepenies’ prose.

Alexandre Kojève, whom we dwell upon a bit, is also a part of this southern European prehistory that Lepenies would like to call to mind. Kojève was the Russian-French philosopher and Hegel expert whose auditors numbered Hannah Arendt and Raymond Aron. In a position paper directly after the Second World War he advised French politicians to jettison the nation-state and strive to achieve a larger federation of states – namely a Catholic empire latin together with Spain and Italy so as not to be condemned to a merely supporting role in European affairs. It was this past spring that Giorgio Agamben, the Italian in Paris, took up once more this idea of a French-Spanish-Italian confederation so as to throw a spoke in the wheel of German dominance in Europe – an idea that Lepenies found to be dated but fascinating all the same.

In contradiction to a traditional German penchant for separating culture from politics, Lepenies believes that the two are not divorced from one another but must be taken together as the basis for any bourgeoisie worthy of the name. Why not take the lead from the French – voilà! If their politics were only half so intelligent as their debates – if these radiated only a scintilla of what Lepenies reads every Thursday (“The most glorious day in France!”) with his head sunk in four political magazines and already looking forward to the weekend editions on Friday!

We arrive back at the Europe of today. Lepenies: “When Greece’s President Karolos Papoulias replies to a rebuke of the German Finance Minister with the words ‘Who is Herr Schäuble to give us a lesson!’ then what you have here is civilization calling barbarism to task.” The thrust of this statement is not to shield the Greeks from legitimate criticism but to make clear the historical wounds that they have had to bear. When seen from this standpoint, Nicolas Sarkozy’s pet idea of a Mediterranean Union was not merely some personal whim of his but boasted a long prehistory. Of course Angela Merkel coolly dismissed the plans of her friend Nicolas and they came to little.

Lepenies is not a man for melodramatics, not one to brag about his oh-so daring theses, yet he has nonetheless remained an engaged intellectual. And despite his valuation of the middle ground, when a clear position needs to be taken he comes down on the side of a liberal-cosmopolitan European republic that is genuinely outraged when African refugees drown in Mediterranean waters.

Who then but France and Germany can pull off the complicated integration of eastern with western Europe? Yes, assuredly, that venerable pairing, he responds, but the “excluded third party,” namely Poland, is also urgently needed. And after Europe’s renaissance of 1989 it became quite clear to him that the “Weimar Triangle” of Paris, Warsaw and Berlin had to be urgently regenerated. It was no accident that he as Rector of the Wissenschaftskolleg, after the “unprecedented occurrence” of the fall of the Berlin Wall and subsequent unification of Europe, had helped to bring into being successful spin-offs of the Wissenschaftskolleg in Budapest, Saint Petersburg, Sofia and Bucharest.

Careful and diplomatic, as is his wont, Wolf Lepenies states that he still does not discern any “schism in Europe,” and what he hopes is that Angela Merkel will use her new term in office to go down in history. In his view the goal must be to move past austerity policies and, in addition to the structural reforms, work together with François Hollande in developing a program that promotes growth, assists European youth, and all of this naturally hand in hand “with a certain monetary discipline.” He believes that “we have more than enough intelligent people in both countries” to excogitate such – a kind of Marshall Plan, if you like, whose historical success was not owing primarily to money but to the “extended hand of rapprochement.”

Lepenies is also a newspaperman – and how. He writes about many things because many things fascinate him. Including sports. On his iPhone he naturally has an NBA-app that gives him the latest scores from America. Recently he has written about Dirk Nowitzki of the Dallas Mavericks, who is not a “star” but a “great.” When a great – this is how the article ends – achieves deserved success under adverse circumstances, we are moved by the feeling that there is indeed moral justice in the world.

Now I’m looking at an essay in Die Welt by Lepenies in which he discusses Pierre Rosanvallon, who has written the “true novel of society” – an historian who advocates a return to centrist politics and brought to life a “Parliament of the Invisible” as an antidote to flights into extremism. Whereas Lepenies’ hero, the critic Sainte-Beuve, lamented the advent of a literary democracy in which writing is no longer a mark of distinction, Rosanvallon hopes for a revivification of democracy through a society of writers. Lepenies refuses to betray where his true sympathies lie.

But he has always opposed this flight into inwardness, this Sonderweg or special path of German bourgeoisness. Meanwhile, in his view, it would seem that this inward flight has been attenuated somewhat. But are not the Germans playing a very dominant role in Europe, while remaining heartily unconcerned about French sensitivities? And how to view German conditions in 2014, this strange mixture of influence through sheer economic might and an apolitical stance, as if it were not the public but politics itself that was de-politicized? How can the new restraint of intellectuals be explained and what does it mean when interventions are allowed, desired, and yet ineffective?

Somehow Wolf Lepenies stands athwart such tendencies. Whatever tack the Republic takes, he unobtrusively opposes withdrawal and something like the storming of the Bastille clearly goes against his grain as well. In his own person, in his own idiosyncratically insistent manner, he shows what he means by engagement, attitude and decency. And he calmly and indefatigably uses literature, philosophical texts, essays, and words as sociological and contemporary study material so that one might occasionally fall prey to the thought that he lives in a world of aseptic superstructure lacking any real social substance. Intelligent critics – and it is only these whom he takes seriously – have reproached him with this, and he concedes that “there is some truth to it.” But his conscience, he adds with a twinkle in his eye, “isn’t so bad that I want to correct the matter.”

The novels and the philosophical or literary writings from his beloved nineteenth century in France or from the twentieth century on either side of the Rhine themselves detail social conditions, and the industrial pre-modern age is disclosed to careful readers, the focused reality of Europe inclusive 1914/1918, the emergence of southern European fascisms, the various political and social designs for the future – the whole kit and caboodle. Surely Lepenies the “author” (sometimes he also calls himself an “intellectual historian”) planes off much that is entailed in a nuanced view, but this does not mean that Lepenies the “sociologist” does not always have this planed-off material firmly in mind. All he wants is to write lucid and well-wrought texts. He writes and speaks more glibly about certain matters than they would sometimes seem to warrant, so that one can often only guess at the complexity behind the polished words. You must draw your own conclusions – and Lepenies expects you to.

The ex-Rector Wolf Lepenies says that these days he has no duties but only rights at the Wissenschaftskolleg – “although I thought the post was wonderful.” He enjoyed being an academic organizer, and he is by nature someone who likes bringing divergent genres and disciplines together – whether or not he occupies a particular post. As far as Lepenies is concerned, the glass is always half full. That too has always been the case. The new openness after 1989 – what an opportunity! He foresaw the conflict with Islam, even if no one could foresee the attacks in New York on 11 September 2001. “Five years previous, not five minutes afterward,” says Lepenies, the Wissenschaftskolleg had already dedicated itself to the theme “Islam and Modernity” – which in the meantime has become “Europe in the Middle East – the Middle East in Europe.” He counts this among his real achievements during his fifteen-year tenure as Rector. As for his present-day role, he alludes to a phrase of Isaiah Berlin’s that he is “a taxi – I come when I am called.” He is always pulling such apt lines out of his hat.

But I am not here concerned with legacies and his role as taxi – I have another agenda. In 1969, Wolf Lepenies’ doctoral dissertation appeared as a book with the title Melancholie und Gesellschaft (Melancholy and Society). There are books in which everything is secreted away and then emerges and unfolds over the course of one's life – and it seems to me that this is one of those books. It is his The Tin Drum, his Jenny Treibel, his Henri Quatre. I reread it before paying my visit to Lepenies. 1969! The zeitgeist was one of upheaval and utopian visions, but as if he couldn’t be touched by all that, Lepenies followed his own unique path – melancholy and the “interior” as a defense against everything visionary and overreaching – pre-modernity as the true subject while those in the outside world talked themselves blue in the face about the future society and the crisis of advanced capitalism! At the time one could already sense his admiration for the autonomous individual – an admiration which has remained with him. A man of both the spoken and written word, back then Lepenies became acquainted in his own quirky fashion with La Rochefoucauld, Paul Valéry, Dieter Claessens (his doctoral advisor), Arnold Gehlen, Albert Camus, Denis Diderot, Sören Kierkegaard, Theodor Geiger, Robert Burton, Walter Benjamin... This intellectual talent pool contained or at least implied everything that would later become fundamental themes for him.

The more that one reads, the more deeply one is sucked into a world, if only in a suggestive way, where the boundaries are blurred between conservative and progressive, modern and anti-modern, inside and outside. And does not this glimpse into an iridescent, multi-level, polyphonic intellectual world impart a certain understanding of the world we live in today – the world of 2014? But increasing our understanding, providing life-wisdom, is indeed the job of intellectuals, as Lepenies once noted. His contribution in this regard was complete with Melancholy and Society, a phenomenally brainy and stimulating classic that causes you to inadvertently ask yourself where precisely our Republic of the Grand Coalition finds itself along the spectrum between retreat into a politically weary inwardness and breaking out of its supposed “complacency” at the international level.

More on: Wolf Lepenies

Images: © Maurice Weiss