William Marx - The Rising of Kaspar Hauser: the Premiere of Hans Thomalla´s Opera at the Theater Freiburg

by William Marx (Fellow 2014/2015)

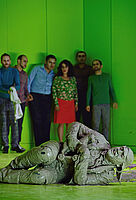

There is at first a kind of green cube at the back of which eight figures are stationed, people like you and me, in shirtsleeves, in turtleneck, in flower-print blouse. They are waiting for we don’t know what. Apprehensive perhaps.

During this time the spectators quietly seat themselves, a bit more smartly dressed than the figures on the stage. Even Onur has abandoned his preferred sweater – which would have come in handy on this cool April evening – so as to style a jacket. I see him with Monica some rows back and I give them both a wave. I know that the others are also here, invisible in the darkness of this grand auditorium of Freiburg im Breisgau Theater but no less present and attentive to that which is to shortly unfold. Martin and Barbara, Philip and Christiane, Veronica and Andrei, Andrea and Wilhelm, Flo, Gilles, Berta, Brandon, Ingunn, Sianne, Simone, Reinhart – they have come from all parts of Germany, from France, Switzerland, Norway, Romania, and the United States. Some of us did meet the day before, in the Café Schmidt, seated around several much-contested slices of Black Forest cake (the best that I have ever tasted; the capital of the Black Forest also deserves to be capital of the homonymous cake) or at the Oberkirch, celebrated for its wild game and its trout au bleu taken from the fish tank and boiled straightaway within the protective shade of the cathedral.

And of course Hans Thomalla, who invited all of us to the performance of his second opera Kaspar Hauser. We followed its genesis in the course of the previous year, filled with wonder to see the development of a work (right under our noses!) of such magnitude and also extremely curious to discover, after the lapse of only several months, the result of such patient writing and composition. This Kaspar Hauser – was it not, to a small degree, the child of us all? Did we not assist in its gestation? Our cultivated conversations (as to be expected), our intelligent suggestions (the least we could do), the magnetism of our very presence – did not all this make a more or less decisive contribution to the begetting of the work? All Fellows flatter themselves that they have participated in a crucial way in the work of their Co-Fellows. That which follows is nothing less than a puncturing of this sweet illusion.

On this 9 April 2016 we really saw – we the public, the Fellows, the figures on stage – Kaspar Hauser rising. Literally rising. Emerging from a big hole made suddenly visible – the opening to some unknown abyss; a sea of mud and muck from whence an unidentifiable being materialized with difficulty, a chthonian creature, powerful, gigantic, who at first knew only to utter two words, repeated ad nauseam: Kaspar Hauser.

Utter, or rather, sing them. For unlike the Nuremberg bourgeois who first encountered him in May 1828, unlike the audience itself, Kaspar Hauser does not speak but sing; and the voice of this massive being, intimidating and disquieting, is that of a countertenor – wispy, seductive, intriguing. Hans Thomalla’s indisputable stroke of genius is this lyrical contrast between the protagonist and the other figures of the opera. While these latter express themselves prosaically along a musical line and register that is close to spoken language, while they form a tragic choir of multiple individuals who are sometimes indistinct and interchangeable, Kaspar emerges as a true operatic hero, endowed with a singing that is immediately recognizable due to its borrowing from the great tradition of eighteenth-century castrati. The role requires an exceptional singer – in this case a Catalan by the name of Xavier Sabata who performs on the greatest stages of the world and who possesses an incomparable vocal and stage presence.

In three acts the opera recounts the true history of those five years when Kaspar Hauser evolved among the honest citizens of Nuremberg and Ansbach, inspiring curiosity, disgust, compassion, fondness, hatred. So many contradictory passions to set the public aquiver – like a string that the composer plays like a virtuoso with discrete support from the orchestra, which he handles in a fluid fashion and with little sophisticated touches that give the singers the most beautiful parts, except for certain instrumental passages that are particularly evocative. An opera is first of all about emotion – both as librettist and composer, Hans Thomalla is master of them all, and Kaspar Hauser has some very intense moments, such as those scenes of affection between the savage young pupil and the teacher Daumer who welcomes him into his home and who is subtly embodied by the tenor Christoph Waltle; or the love felt by Karoline Kannenwurf for the hero; or the dream of this latter who believes – reality or illusion? – to recall his childhood in a beautiful palace with a woman in white and a man in black; or the death of Kaspar, of course, through stab wounds administered by unknown knives, then his metamorphosis into the statue which today adorns the streets of Ansbach.

The piece’s dramatics are yet reinforced by Frank Hillbrich’s simple and efficacious staging – a circular hole filled with mud, in the middle of a stage that is clear and bare. Bit by bit the mud cakes everything – the flooring, the walls, the singers – mud that has been provided by Kaspar, the implacable strangeness of an enigmatic apparition that comes to disarrange a world too clean, too sure of its comfort, too anchored in its certitudes. One cannot help thinking of those hundreds of thousands of refugees who are landing on European shores and who in present-day Germany are finding a help similar to that which benefited Kaspar Hauser – and of the equal number of discussions and debates they have provoked; yet one might dare hope that their story will have a less tragic issue.

The mud was the great victor of the evening, and its anointment spared neither the conductor Daniel Carter nor the composer during the bows and final applause.

No mud, however, during the fête given in honor of the show’s organizers and performers, but rather beer and champagne which flowed in streams. The Fellows thus had opportunity to share their joy and other emotions with Hans. None of us had imagined the final form this piece would assume, even though developed at our side, among us, and before us during a famous colloquium. All things considered, we were no better informed as to what was going on than the eight figures at the start of the opera, leaning up against their green cube, ignorant of what would be emerging from the hole in front of them. No, we were decidedly not the inspiration for this work, neither its co-authors nor its sponsors nor its godparents. We were solely its admiring witnesses, just good enough to proclaim this: Kaspar Hauser is dead – long live Kaspar Hauser!