Return to Gdańsk

Paweł Machcewicz Fellow 2017/2018

Eight months after his dismissal by the Polish government, the former director of the Polish Museum of the Second World War guides a group of Fellows through a controversial past.

Returning to places where one strived under different circumstances might be imagined a risky endeavor. Especially if those places meant quite a lot to the person involved and parting was not exactly voluntary.

The train from Berlin to Gdańsk arrived late on the evening of 17 November 2017. Our group of Wissenschaftskolleg Fellows had only time and energy for a short walk in the old section of the city. From a distance, standing on the Green Bridge over the Motlava River, I showed my companions – the monumental silhouette of the Museum of the Second World War shrouded in darkness but still dominating the skyscape of old buildings and churches.

The next morning was sunny and brisk and we embarked on our visit. After entering we descended several levels into the permanent exhibition area. I had tried to conceive of this moment ever since agreeing to show the museum to the Wiko Fellows and other friends from Berlin. It was Andreas Staier’s idea. He had followed the story of the museum in the German media when I was still its director and struggling to open it to the public in the face of government countermeasures. Originally the Fellows and I had been planning to visit in October but tickets for the museum were unavailable at the time and we were forced to postpone the trip one month. This delay was frustrating since by the time we finally arrived the original shape of the exhibition, i.e. as I had left it, was no longer to be seen; two weeks before our arrival in Gdańsk, the government had introduced their initial changes to it.

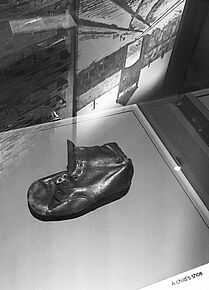

Entering the museum for the first time since my departure last April was a very interesting and to some extent unpredictable experience. I know every part of this building and especially the exhibition on which I had worked for eight years. But my first feeling was of having entered alien territory. I knew very well that for the new director and for the minister of culture I had become a public enemy accused of creating an “anti-Polish museum,” which allegedly neglected Polish heroism and martyrdom, my having from the beginning acted on “foreign orders.” Regardless of the sheer absurdity of such accusations, those initial moments in the museum were simply unsettling. It was only after we had started our tour of the exhibition, and I began explaining its concept and artifacts, that other feelings gradually prevailed. I saw the interest and engagement of my companions growing with every step we took. Because most of them were not historians, in a way they were those “typical” visitors for whom the museum was created. I felt gratitude toward these people who had compelled me to journey to Gdańsk and revisit my museum. Without their encouragement I would never have ventured such an undertaking. And now I experienced the joy and satisfaction of explaining that work which I had for so long pursued together with numerous other historians, many of these my friends, and most of them meanwhile also purged from the museum. Telling the stories of artifacts that we had collected all these long years was like disclosing the inner life of this exhibition, which was invisible on the surface to the uninitiated.

These positive feelings were brutally violated at end of the tour. Even from afar, before entering the last room of the exhibition, I heard certain strange disruptive voices that were in striking dissonance to the museum’s whole message and artistic language, most of it still intact despite the fortnight of alterations; in fact this was the first really invasive change introduced by the museum’s new masters. Originally the visitors, just before leaving the exhibition, had watched film and photographic footage documenting the wars and other conflicts and violence after 1945. The last scenes showed ruined Aleppo and Donbas, wounded and despairing civilians, children, refugees. It was a reminder that war and violence were not some distant closed chapter but an integral part of the human condition. This element in particular was criticized by the right-wing in Poland as too “universalist” and insufficiently “national.” Now it had been replaced with this four-minute cartoon that resembled a computer game and pretended to depict Poland in the twentieth century. In a way it had nothing to do with real history but was a rather bombastic piece of propaganda boasting of our exceptional victories and sufferings. I felt that my ideas had been raped. Some of my companions, though certainly less attached to the exhibition than I, had similar thoughts and could not watch the film to its end.

We left the exhibition, having spent over four hours there, and met with the architects who had designed the building and who now shared with our group the meaning of its architecture. How enlightening to go outside and listen to their comments regarding the various elements of the building as dusk slowly crept and that fading sunshine gave the whole scene a veneer of unreality. The last stage of our trip was the visit to a “vodka joint” in the old part of town and whose entire design and purpose was to resemble those cheap bars from communist times. That drink which had soothed tortured souls in Eastern Europe all these centuries was badly needed.